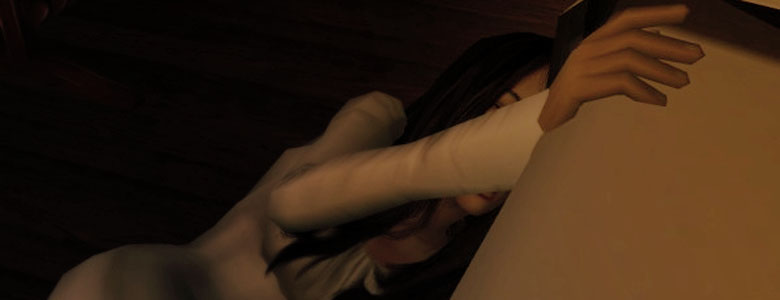

Flann stumbles and falls again

Flann had been running. She was breathless and panting, her throat was ragged from gulping cold air, and when she tried to sit up, her knees shook spastically beneath the tented blankets.

She had been running and stumbling, falling down, getting up, and falling again. In the dream there was no end to it.

Waking up was not a relief. She had not been running from something: she had not escaped. She thought she must have been running towards something – something unattainable, but necessary.

Or perhaps she had only been running to run. Certainly she had nowhere to go.

Even candles were condemned to a sad fate if left in Flann’s unworthy care. Unlike Cat’s or Lena’s little bedtime tapers, Flann’s candles were acquainted with the darkest hours of the night. Over and over they were lit, left until they guttered, snuffed out, and lit again. There was no end to it but the dawn.

Over and over Flann would wake and rise and walk, shuffling from south to north and back again, pacing endlessly like a cottar’s mare between the hills Osh had painted on the eastern and western walls.

There was nothing on the north wall and nothing on the south; Osh had never painted for her “what she most wanted” to see upon waking: she had never told him what it was.

He had once offered her a little house such as he had painted on his own wall – or at least she thought he had. He had even offered her a house such as he had painted on hers: his idea of the houses of her home, with their peaked roofs and ponderously thick walls, such as houses must be in a country where the most abundant crop of any field was its stones.

Flann leaned over her bed and stroked her fingertips over the roofline, trying to read what he had written there, trying to find the little heart hidden in the thatch. She had nearly rubbed the paint away with her trying.

His head was behind the wall, she knew, only inches from her hand. She tapped, but she knew he would not come. He would not come for her tapping if he did not come for her sniffles or choked-off sobs, night after night, as she woke and cried and slept and woke to cry again.

There would be no end to it. He had suddenly begun coming to comfort her crying, during that week or ten days after she had learned of the death of her father, but he had stopped as suddenly: ever since she had failed to stay with him on the one night they had been alone together – on the one night he had said they were not alone.

He would never marry her now. He did not seem to know there was an aloneness beyond that of being trapped in crowds. Again she had thought she had found a sure love, stability, and security for herself, so that she could give the same to her baby. Again she had fumbled and failed. It would never end.

She did not think she could go on. Even if she could, she would never arrive anywhere, living as she did: running and stumbling and falling, getting up and running, falling, and getting up again – not with such a burden of anguish to heave up every time. It would have to end.