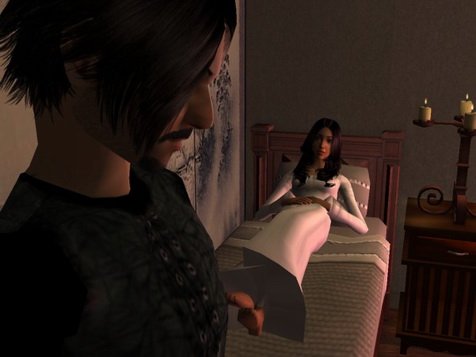

“Good morning, my darling.”

Paul and Catan had eyes only for the baby, but Osh had been more eager to see Flann.

All through the night he had been certain she was dying, for her screams and moans had been the most terrifying sounds he had ever heard. Cat had assured him that this was normal for women, and she had even mocked his fright and made him feel rather foolish.

He no longer felt foolish for having worried.

She murmured a “Good morning,” in reply to his, but that, and the dawn light sparkling in her dark eyes, were all that made her seem alive.

She had been dressed in a clean, soft nightgown, and her body had been bathed and her hair combed. It was all as one would have done for her corpse if she had died. And she stared at the blank, gray wall with the unseeing eyes of the dead.

His own family had said he looked like a living corpse for weeks after Sora had been killed. He had never seen that look, but he who had looked it knew Flann’s heart was broken. He thought it such a shame that hearts could not be healed – for her and for him both.

“Come look at this baby,” his son whined. “You’ve been staring at Flann for months already.”

“I don’t believe any baby is prettier than she,” he protested, but he went to look all the same.

He had been promised a baby that would cry all the time, but in the hour since her birth, except for the cry for air that even elven babies made, he had heard only Cat’s cooing and chattering.

Now, as Cat lifted her from the cradle, she made a little cough that sounded very much like Cat’s customary “Ach!”

“So much for me!” Osh sighed. “Does she speak only Gaelic?”

“Aye,” Flann said dully.

Cat cooed, “Auntie Cat has been talking to her for months already, hasn’t she, wee angel?”

“Oh! That was English,” Osh smiled. “There’s still hope for Osh.”

“Come over to the window,” Cat said. “She likes the light, silly wee girl. One would think she’s been waiting nine months for nothing but that.”

“I thought babies didn’t like the light,” Paul said.

“What do you know?” she asked.

“Because our ladies have their babies in a dark room, so they aren’t frightened.”

“What do they know?” she laughed.

“So why do babies always want to come at night?” he challenged.

“How do they even know when night is? Here, darling, you go see Uncle Osh. He wants to hold you.”

Osh’s arms and shoulders stiffened, preventing him from taking her. His voice too was stiff and hard when he said the only thing that came to mind. “I am not her uncle.”

“Ach! That’s only something we say.”

“Flann is not my sister.”

“We know that, Osh!” Cat laughed. “What would you rather be? The grandfather of her?”

“She already has an uncle.” He glanced up at Paul.

“She already has a grandfather, too! What else does she need? Here, take her, Osh. Don’t make me think you’re scared of little toothless babies, or I’ve some bad news for you!”

He was thinking that it was a father she needed. But he could not say that.

Instead he said, “Oh! If she has no teeth, that is another thing.”

Fortunately his arms were functioning normally again.

He had not lost the habit of holding babies. There was nine-month-old Penedict, of course, but also a number of younger babies of men who had been ill and whom he had helped to breathe.

Still, there was something about a newborn, with her squinty, staring eyes, and her limbs that hung limp from her body, but with a springy curl drawing them up against it.

“Well, say something, Osh!” Cat commanded. “Flann will think there’s something wrong with her.”

“There is nothing wrong with her,” Osh said dazedly. “She is beautiful very much, like her mother.”

“What is her nature?” Paul asked him in their language.

Osh sent him a brief scowl. He was annoyed to be interrupted, but more so to be asked to gaze uninvited into the essence of this child who was not even his own. His son seemed to think that their situation exempted them from the proprieties of their people, but Osh did not agree.

“I am not the Shalla,” he grumbled. And then he answered the question: “Light. Radiance. Invent your own word for it. I haven’t one.”

In any case it was the nature of the baby’s mother he most wanted to know, but he would have followed her into her bath before he would have so violated her.

“What did you say?” Cat asked uneasily.

“Your husband is making fun of me again,” he lied.

“Why is he ‘my husband’ when he’s rude and ‘your son’ when he’s clever?” Cat smiled.

“What will you name her, Flann?” Paul interrupted, perhaps to avoid any unflattering discussion of himself.

“Ach!” Cat turned to her sister in dismay even before she answered.

“Liadan,” Flann said.

“Sister…”

Osh wondered at Flann’s sullen face and at Cat’s distress. It must have been an unfortunate name, but he did not know enough Gaelic to guess why. In his language it was a strange, sad phrase: “Rain – whose?” And the word for “sorrow” was the same as the word for “rain”.

Osh looked at Paul to see whether he might have suggested the name to her, but Paul was already looking at him with the same question in his eyes.

“What does it mean?” Paul asked.

“It is a name from an old, sad story,” Cat said. “Darling, it’s not a pretty name for a baby, is it?”

“It’s the gray eyes of Liadan she’s having,” Flann said, “and her mother the grief of her.”

Osh looked down again into the baby’s drowsy face. The eyes were so dim a blue one might have called them gray, like the half-lit underbellies of storm clouds drifting away. Still, only his unwillingness to hurt Flann prevented him from saying what Cat immediately did.

“You know a baby’s eyes are not to be trusted, dear. It’s as brown as yours or mine they soon will be.”

“They shall be gray,” Flann insisted. “It’s garbed in gray she shall go, and she has no sister to be saying her nay.”

“Flann, darling,” Cat cried tearfully, “you can’t be dressing a sweet baby in gray!”

“Liadan of the gray eyes…” Flann whispered dreamily, as in a dream that had died. “Liadan of the gray skies…”

Cat continued pleading with her, but in Gaelic now.

Osh turned slightly to let the baby look out at the light she was supposed to love. It was rosy on her skin and pink on the painted mountains of the opposite wall, but he did not think she would be able to enjoy it long. Such a low pall of clouds at dawn promised gray skies and a gloomy day.

Before anyone panics, she is not supposed to be hairless! I don't know what happened to her eyebrows! I did change her skin in SimPE, because she got stuck with Egelric's old skin. (Which is what prompted me to get rid of it, after several other babies with the same affliction.) But I've done that before without losing eyebrows!

I tried putting eyebrows on using the InSim temporal adjustor, but that didn't change a thing. So unless I find out how to add/change eyebrows with SimPE, she's browless.

It actually looks more like a newborn than the usual thick, black eyebrows babies get stuck with. But she would be much cuter with a little dark fuzz on her head. You will have to imagine that for the next 8 months or so. She will have black hair like her mother.