Egelric’s head nodded with fatigue, but he was not yet ready to go to bed. This was perhaps the last night he would spend in this house. Sigefrith had asked him to stay at the castle, but Egelric had preferred to go home, preferred to spend this last night with the ghost of his wife. He knew that when he returned – if he ever returned – she would be gone.

Burning her chest had liberated him in some way and permitted him to dispose of the remaining objects in the house that had been her things, and not theirs or his. All he had kept was a lock of her red hair, in case Finn ever–

But he would not be taking that with him. No, instead he had folded a flaxen curl into a piece of soft leather and tucked that into his bag. He would ride out wearing Matilda’s red band, but she little knew that the color of his true lady was pale gold.

He sighed as he thought of his daughter. She had not liked to see him go. When he had left her with Alwy and Gunnilda she had–

He lifted his head. Someone was knocking urgently at his door. A message from the castle, surely, late as it was.

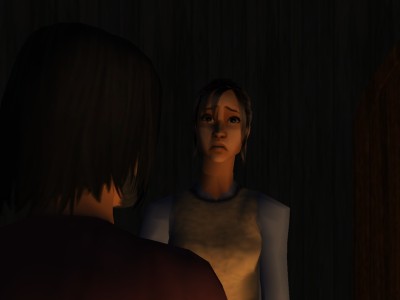

He got up and opened the door onto a pouring rain. “Aye?” he barked. The messenger cringed. Egelric blinked his dry eyes, trying to make out the face in the few rays of the dim red firelight that glowed behind him.

“Gunnilda?” he cried. If she was here now then – “My Baby!”

“No, Egelric,” she sobbed, “She’s sleeping. Please let me in.”

“For God’s sake, woman, get in here then! What’s happened?”

“They’re all sleeping,” she babbled hysterically. “Finally got them all to sleep.”

“And? Why, you’re soaking wet! Get in here by the fire. Here’s a towel to dry your head. You don’t even have a cloak! Are you mad? In your condition?”

“I had to say goodbye,” she whimpered.

“Goodbye?” he repeated, dumbfounded. “Didn’t we say goodbye a few hours ago?”

“That couldn’t be goodbye,” she sobbed.

“What? Woman, you’re overwrought. This is no good for you or your baby. Now sit in this chair and calm yourself and tell me what you’re doing here.”

“Egelric,” she said miserably, “What if you don’t come home? What if you don’t come home, and all I had was that goodbye in my kitchen, with Bertie and Wynn and Baby all tugging on your hands, and Alwy snivelling in the corner, and me trying to smile like a little fool so as not to cry? I would regret that all the rest of my life! I would die!”

“Well, at least you wouldn’t regret it very long, then,” he snapped.

“Oh, Egelric!” she sobbed into the towel. “You’re so hard!”

“Oh, Gunnilda,” he sighed in exasperation. “I don’t know whether to laugh at you, or yell at you, or cry with you. Is this the goodbye you wanted, then? Sitting there, soaked to the skin, your hair plastered to your face, your eyes all red, and crying into my dishtowel? And my sarcasm?”

“Not neither!”

“Come, Gunnilda,” he said more gently. “I shall have to laugh. Do you have any idea what you did to your hair when you toweled it off just now? You look like you have Alwy’s black rooster’s tail tied to your head. Your hair is sticking out in every direction except down.”

“Oh!” she huffed and started picking out her pins.

He leaned against the fireplace and watched her. Such a silly little bird she was. But he was always surprised at the transformation on the rare occasions when he had seen her with her hair down. That black hair seemed to be a magical cloak that turned her into somebody else entirely. Did Alwy notice that? Or was he too well acquainted with both of these women to remark the difference any longer?

“Is that better?” she sniffed.

“Better, but you are still rather ridiculous, you know.”

“I can’t help that,” she pouted. “That’s just the way I am.”

He laughed. “Now that is better.”

Gunnilda smiled sadly and looked down into the fire.

He was still rooted to the fireplace, and she still seated in the chair, and as he looked at her across the space between them he wondered suddenly what would happen if they lost these objects that anchored them and floated free. But then – the chair and the fireplace were really airy nothings compared to what truly held them down. And so, he thought, he must be terribly tired to be thinking such things. He would have to convince her to leave, before–

“You look tired, Gunnilda,” he suggested. “It was wrong to come out here like this. You should be snug in your bed right now. Why don’t we say goodbye now, calmly, and then you take my cloak and go home?”

“I can’t,” she said, her chin trembling. “I can’t.”

“You can’t go home?”

“I can’t say goodbye,” she said, beginning to cry again.

“That’s why you came, though, isn’t it?” he said evenly.

“But this is – too hard, Egelric. Last time you was just going to Scotland to talk. This time you go to fight. And if you fight you may die.”

“You’ll take care of Baby for me, though, if I do, won’t you? You love her, don’t you?”

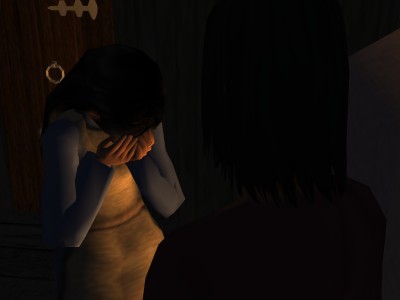

“Yes, of course! But I also – ” She abruptly hid her face in her hands.

“Then take care of her, and love her. For my sake.”

He stood and watched her silent struggle with herself. He longed to pry her hands away from her face – there was something so heartbreaking about the sight of the little woman suffering alone, doubly hidden behind her hands and her curtain of dark hair. But to do so he would have to leave the fireplace, and he would have to touch her.

And then a sob of anguish wrung her, and he moved instinctively to protect her. He grabbed her wrists and yanked her hands away from her face, as if it had been her own hands that were hurting her. And she blinked up at him for an instant before flinging herself at him.

Oh, what did it matter? Perhaps she never would see him again. If she wanted to cry her eyes out on his shoulder, then he would let her. It was less cruel than coolly watching her from the safety of the fireplace corner.

He held her until she stopped sobbing and laid her wet cheek against his neck, as women and tiny girls always did in the end.

“Now,” he said, gently unwrapping her arms from around him, “where’s that towel?”

“Oh!” she sniffed as she dried her face. “Why am I always such a fool around you?”

“Now, that’s not so,” he soothed. “It only seems that way because I’m so reasonable.”

“Pish!” she scoffed and threw her arms around his neck again.

Well, let her look her fill, he thought, the poor funny bird. Let her memorize his face, if she would.

Her own round face glowed like a golden crescent moon in the dim light; her dark, slanted eyes were red with tears, and yet she smiled up at him with a radiance that lit and warmed him more than the fire. He would not forget hers, either.

“Is this the goodbye you wanted?” he asked softly.

She nodded, still smiling, though her eyes sparkled with gathering tears.

“You know I can’t promise you anything,” he continued. “I can’t even promise you I will come home.”

“I know,” she whispered, her pretty lips trembling.

He closed his eyes and made an effort to collect his thoughts. He was too tired to handle this the way he ought. He would have to send her home.

“Then I can only say goodbye,” he said. “Perhaps I shall see you again soon, but now you must go. If Alwy wakes he will be sick with worry over his wife and child. As I would be in his place.”

She turned away, nodding mutely.

He took his rough old woolen cloak from the hook and wrapped it over her shoulders, thinking as he did of the contrast between dark little Gunnilda, who snuggled gratefully into the humble plaid, and his red-haired wife, who would stand tall and wait for him to drape her embroidered shawl over her proud shoulders as if she were granting a favor. He shook his head grimly. She was still haunting the house tonight.

“Come,” he said, taking down for himself the cloak he was to wear tomorrow. “I want to see you safely home.”

The rain was still pouring down, and he walked her as briskly as he dared down the muddy path through the woods.

“I shall wait out here for a little while,” he said when they reached her yard, “should you need me for anything.” He was thinking he might need to explain to Alwy, though God only knew what he would say.

She took a step or two towards her door, but turned and looked back at him, hesitating.

“Go in,” he called over the drumming of the rain. “We already said our goodbye. Don’t spoil that one by saying it again. I’m already gone.”

She sobbed and ran for the house.

He waited under a dripping pine until he was certain she must be in bed – or, if she had had to explain to Alwy, she had done so without needing to turn to him. Perhaps he would never know what had awaited her behind her door. Perhaps–

He turned and began the trudge back up the hill to his farm, burdened by the weight of a new idea. He had been too occupied in observing her own little drama to think of what it meant for him – for if she never saw him again, then neither would he see her.

You can really tell they love each other. I kept expecting them to kiss, but I knew they wouldn't because they have never gone that far in their relationship...only hugs.