Osh stopped just short of the cottage and lifted his hands to halt Vash and Shosudin behind him.

“Stand clear if you value your noses,” he warned.

His voice was low and sounded weary, but there was something comical in the way he leaned forward, balancing like a stork on one leg, to knock gingerly at the door. Shosudin looked aside at Vash to see whether they were supposed to laugh.

Vash was not laughing.

The door opened abruptly, though not violently enough to have threatened any noses.

The woman who stepped out onto the snow was small and plain and inconspicuous, as most women were to Shosudin’s eyes, except for the wiry heap of red hair piled upon her shoulders. The light of the open door made it glow like golden fire, and for a moment he thought her almost as magnificent as Dara.

After a quick glance at the other elves she turned her narrowed eyes on him, as though she knew what he was thinking, and she did not approve. She stepped out of the doorway, and her hair went dark.

Osh began, “Good even – ”

“You said one elf!” she snapped.

The snow creaked as Osh or Vash shifted his weight from one foot to another, but Shosudin was paralyzed by the woman’s stare until Osh laid a hand on his shoulder, and he could at least breathe.

“I bring Shus to help,” Osh said, “but I bring Vash because he is Kraaia’s special friend.”

Shosudin glanced away from the woman long enough to take in Vash’s face. Vash was not smiling, and by the time Shosudin looked back to Ffraid, her scowl had soured into a look of faint disgust.

But she only turned back into the house, muttering, “Well, come in already so’s I can shut the door, or you can just bring in more wood yourself.”

Vash came back to himself at once and put on his customary charming smile. Shosudin’s tense shoulders relaxed slightly in relief.

“I shall gladly do both!” Vash called over Osh’s shoulder as they filed inside.

Osh went directly off to the right, but Vash followed Ffraid into what appeared to be the kitchen-half of the small house.

Shosudin ducked through the low door and pulled it softly shut behind him. He stopped there, uncertain which way he ought to turn.

The woman squatted before the fire and poked it with a stick. “Anyone see you comin’ here?”

“We’re elves,” Vash smiled. “Nobody saw us.”

“We’re elves,” she muttered to herself.

“Can I get you – ”

“How old are you?” she interrupted.

Vash hesitated. “Ah… twenty-three.” He glanced expectantly over his shoulder.

Shosudin had been watching Osh bending low in the other room, trying to wake the hoarsely breathing girl in the bed, but he hurriedly attempted to figure out his own age as men reckoned time.

Ffraid brushed off her hands and stood. It was Vash she was asking – she was not looking at Shosudin at all.

“Ain’t that a bit old to be the special friend of a twelve-year-old girl?” she demanded.

Osh was clucking and crooning over the bed as if it were a cradle. Kraaia awoke whimpering, like a baby.

“Not that sort of special,” Vash smiled. “I only met her three nights ago.”

“Then how did you get to special so fast?”

He laughed and announced, “She stabbed me!”

Shosudin winced.

“But I ate her cheese,” Vash added, “so we are even.”

When Ffraid failed to smile he turned to grin at Shosudin. Shosudin was just making up his mind to frown warningly at him when Kraaia moaned in the other room – “Osh, it hurts…”

Vash’s smile rippled no more than a frozen lake. Shosudin stared blankly at him in disbelief. He knew his friend was neither hard-of-hearing nor unfeeling. Then it occurred to him that the smile must simply have been false all along.

“I will endure any sort of abuse for the sake of cheese,” Vash laughed.

He stared at Shosudin as though pleading for some sort of confirmation or reply. Even Ffraid turned her baleful gaze from Vash onto him.

Shosudin said gravely, “We brought you a deer. It is with the horses in the shed.”

“A deer!” Ffraid squawked. “Godamercy!”

“Also a wine,” he added.

“Some wine, beetlehead,” Vash said.

Shosudin endured the correction without comment. Vash had gradually stopped speaking English with his friends some time ago, and he had never said why.

“And cheese!” Vash laughed. He stuffed his hand into his cloak and twisted his way past Shosudin into the other room.

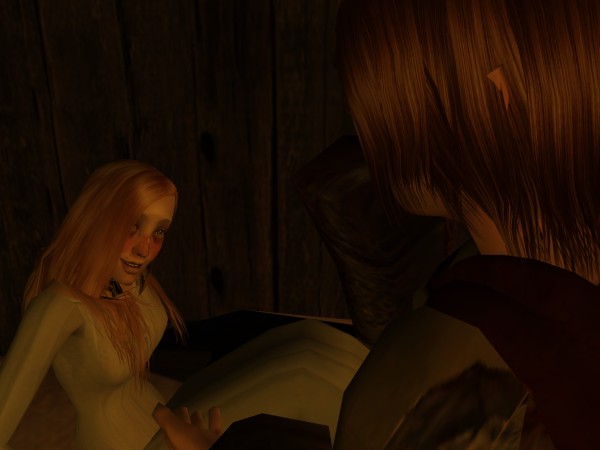

The girl lifted her head off the pillow, and Shosudin had his first glimpse of a cadaverous face. Vash laughed on as though he were blind.

“Look what I found!” He pulled out his wheel of cheese and waggled it accusingly at Kraaia.

Astoundingly, she smiled. “You found it!” she croaked.

“Next time, you must hide it better than in the one place I know to look!” he teased.

“A deer!” Ffraid huffed behind Shosudin. “So now I’ll be a poacher too!”

Shosudin turned and opened his mouth to ask her what a poacher was, but she barked, “Out of my way!” and barreled past him on her way to light a lamp.

Osh wandered dazedly from the bedside to the fire, picking at the buttons of his cloak as he went.

His face hinted that she was worse than when he had left her. Certainly she was worse than he had described her. She was worse than the worst of what Shosudin had imagined. She looked like a corpse that had been left to lie face-down until the thickening blood had pooled in the face and hands, and then flipped over. He had never seen her like alive.

Vash hid his cheese in his cloak again and turned to wave Shosudin closer. “Come in, Shus! There’s a young lady here who is so happy to meet you!”

Kraaia sat up and smiled at him. Her bloated cheeks looked as if they might burst from the strain. “Did you heal him?” she asked hoarsely.

Shosudin tried to smile. Very deliberately he propped up the corners of his mouth and squinted his eyes, though he feared he looked like a lunatic. He wondered how Vash did it so well.

“Did you leave a scar?” she demanded.

Shosudin looked to Vash. His smile twisted and his squinting eyelids fluttered. Vash had asked him to leave a small scar, and now less than ever did he understand why.

Osh said gently, “Shus will not leave a scar, Kraaia.” He seemed to believe she had asked out of fear for herself, but she appeared disappointed at the answer.

“Only one small one,” Vash assured her. “I told you he would.”

Vash and Kraaia tried to share a complicit grin, but her lip split open, and she winced and clumsily brought the back of her dark hand up to blot the blood.

Osh turned abruptly away again. Shosudin heard Vash take a sharp breath, but his smile never wavered, and his breath the girl could not have heard.

Ffraid snatched Osh’s cloak away from him as she stomped past, huffing as though she were reclaiming stolen property. She gave Shosudin a look that made him hasten to open his buttons.

“Come in, Shus, come in,” Vash begged. “Don’t be shy. This is what happens when I tell him you are his greatest admirer,” he confided to Kraaia. “Don’t let it make you insufferable, Shus. If I tell you she is your greatest admirer, it does not mean she does not admire me more.”

“I do not!” Kraaia croaked.

“But you said I was very handsome!”

“She did not see Shus yet,” Osh observed.

Kraaia fell back onto her elbows and said, “Ha!”

“This flea-bitten old badger?” Vash protested. “This bald-tailed squirrel?”

“He’s handsomer ‘n you,” Kraaia said thickly.

“What?”

She giggled, and the sound rippled cleanly like water burbling out of a deep spring untouched by frost.

“I bet some toad made an evil toad-wizard mad, and got turned into you!”

Vash laid his forehead in his long hands and sighed. “And now I must wander the earth kissing toads until I find one which is a pure-hearted toad girl!”

“You must what?” Osh whispered. He looked to Shosudin. Shosudin shrugged.

Vash peeked out at Kraaia from behind one hand and added slyly, “Fortunately I hear they are quite congenial.”

“‘Cept when they pee in your hand!” Kraaia laughed.

“I was about to say that!”

They laughed together until Kraaia choked into a cough that rattled like ice breaking up in her lungs. Ffraid kicked a stool almost against Shosudin’s calves and barked at Vash, “Your coat?”

“Oh – sorry,” Vash stammered. “That is, thank you.”

His hands were clumsy – perhaps even shaking – as he unbuttoned his cloak, but he spoke to Kraaia in an easy tone that seemed neither to draw attention to her painful coughing nor awkwardly attempt to ignore it.

“I shall try to be less funny tonight,” he offered, “if you cannot laugh. I cannot help being handsome, however. You may have to cover your eyes to make it fair for Shus.”

The corners of Kraaia’s smiling mouth appeared on either side of the wrist she held before her coughing.

Ffraid sent a stool skittering in Osh’s direction, but Osh climbed around the head of the bed and sat himself down beside Kraaia’s pillow. He subtly stroked her arm, and her coughing body curled towards his.

“If you want to be less funny, Vash,” Osh suggested, “you should stop telling everyone how handsome you are. Ffraid cannot stop to laugh,” he added with a wink across the room.

“You call this laughing?” Ffraid huffed. “If you ever see me serious, you’ll be sorry!”

She kicked another stool roughly across the floor at Vash, and Shosudin hastened to sit in the nearest chair before she knocked anyone off his feet.

Vash stopped the latest missile with the side of his boot and said, “Thank you,” as if it were quite the customary way to offer an elf a seat. He pulled it as close to the head of the bed as his knees allowed and sat.

Her coughing at last calmed, Kraaia lay back, flushed and panting, with her head leaning against Osh’s knee.

“What are you going to do?” she asked weakly.

Ffraid demanded, “Yes, what are you going to do?”

Shosudin looked down at his folded hands. He did not know what to say. He did not know.

Vash offered, “Shus will simply touch her with his hands, where she is hurt.”

Ffraid snapped her fingers. “And she’ll be healed!” she scoffed. “Just like magic!”

“No…” Vash said. “Not like magic. It is magic.”

Ffraid snorted and muttered to herself, “Magic – in my house! Just what I need!”

“It is not unchristian,” Osh said. “The Abbot said to my son.”

“Oh, the Abbot…” she growled.

Vash caught Shosudin’s eye and asked him in their own language, “Do you want to trade chairs?”

Shosudin hesitated. He did not know how many of their words Kraaia knew, and he did not want Osh to hear what he wanted to say.

“Where should I start?” he whispered, since he dared not ask, “Which parts should I do?”

“It’s up to you,” Vash shrugged.

“No, Vash…”

“It does not matter where you start so long as you reach the end.”

His smile was as unnervingly steady as before. Was it real? Did he truly not understand what he was asking?

Then he added softly, “Make her your masterpiece, Shus. You can do more than you know.”

He understood.

Kraaia whimpered, “What are they saying?”

Osh said, “They try to decide where Shus is starting, Kraaia. Shus, let us say you start with her leg?”

Shosudin sighed and nodded resolutely. A broken leg was a simple, straightforward thing.

“He can heal a broken leg like that?” she asked.

“Oh, can he!” Vash laughed.

“He has rather a lot of practice when he was a boy, with my Paul,” Osh confided. “Sometimes he made it so well, I never knew until Paul told me, a long time after.”

Kraaia giggled nervously. Shosudin pushed the blankets aside and gently lifted the girl’s hem almost to her knees, revealing a crude but neatly-tied splint over one shin.

“Paul was the little baby among us,” Vash said, “always trying to keep up with the big boys on his short legs, always falling into ravines and sticking his foot into wasps’ nests and getting trapped in the tops of trees and so on.”

“He never talks about that!” Kraaia smiled.

“I know!” Vash sighed. “That insufferable goat only tells the stories where he is the hero.”

The angry knot of inflammation was so small that Shosudin almost missed it the first time he passed his hand down the bandages. The ends of the larger bone had been brought so perfectly together that the flesh around them had relaxed and was scarcely swollen.

“And what stories do you tell, Vash?” Osh asked him.

“Not goat stories!”

“Stories where Vash is the hero?”

“Why? Do you know any?” Vash grinned.

Shosudin closed his eyes and traced out the the thinner bone. The pieces were slender and birdlike, more tinkling than chiming, delicate as a child’s but crystalline as a woman’s. However, his every attempt to trace a straight arc from the ends to the broken center met in a tangle – the snapped ends of every hair-thin tube met with some wrong-sized neighbor.

Still, he decided he risked worse if he removed the bandage. The heavy bone could bear her weight, and the the thinner would simply lose some of its spring. He could heal her leg with the splint on. The true question was whether she would ever put her full weight on her feet again at all.

Before he began, he decided he would see what awaited him. He ran his hand down her ankle and over the top of her foot, and gently slid his fingertips into the hollows between her purple toes.

They were dead and spongily unyielding as the toes of a corpse. They were cold and dense as mud.

Shosudin had not wanted to believe they had rubbed her frozen feet and hands and cheeks with snow, but it must have been true. The same people who had so expertly splinted the bones of her leg had killed her toes, grinding her flesh to mush between splinters of ice on the inside and gritty handfuls of snow on the outside.

He did not think Vash understood what he was asking.

He lifted his head to warn him somehow, but Kraaia interrupted something Osh was saying to plead, “Is it going to hurt?”

Shosudin pulled his hand away, feeling strangely ashamed. “Did you feel it?” he asked her. If she could feel her toes at all he would have called it a promising sign.

Kraaia only licked her dry lips and looked fearfully at Osh.

“It is like many things in life, Kraaia,” Osh explained. “If we are brave, we do one thing which hurts a lot for a short time, instead of something else, or nothing, which hurts less but for a long, long time.”

“I know that,” she mumbled. “I just wondered.”

“It will hurt,” Vash admitted, “but you will feel so much better tomorrow. And if it hurts too much, you can always bite down on my cheese,” he winked.

She giggled, and her leg relaxed into Shosudin’s hand. “You would do that for me?” she wheezed.

“Will we be even then?”

“No!” She laughed in wicked delight. “Not unless I lie to you!”

“Ah, I try!” he shrugged.

“Kraaia,” Osh said, “perhaps Vash will tell you a story so you don’t think about your leg. He has a lot of practice at telling stories,” he added with a sly glance at Vash, “since he is always telling stories to his father about where he has been the last night.”

Vash broke into a sheepish grin that looked hearteningly real. Shosudin resolutely wrapped his hands around the splinted leg. He seeped like water down into the shattered caverns of bone. The first throb of pain hummed up the bones of his arm.

“Stories where Vash is the hero?” Kraaia giggled.

“I don’t know any of those stories,” Vash laughed. “I tell my father I did something stupid, so at least I can tell myself I got a scolding.”

“Is that how you live with yourself?” Osh mused.

Kraaia coughed briefly, and Shosudin stopped his own breath and held her leg motionless above the bed, trying to keep himself inside without getting himself too enmeshed with her. Something seemed crushingly fragile about this place.

“Tell me a story where a goat is the hero, then,” Kraaia said.

“You cannot be serious,” Vash groaned. “When Paul has his baby he will be telling those every night – simply listen to him. I have a better idea. I shall tell you a story about a crow.”

“Oh! An elf story?”

“No, an old story of men. It is the story of the fox and the crow. Did you hear this one?”

“Oh, I know this one,” Kraaia sighed. She told Osh, “He wants to tell that story because it’s a story about cheese.”

Osh laughed. Shosudin heard his laughter echoing through the cave, warbling between the thousand thousand pillars like the song of a bird lost miles underground. The rivers behind the walls seemed to surge at the sound.

“The cheese has only a minor role,” Vash protested. “And anyway, Shus hasn’t heard it. Have you, Shus?”

Shosudin would know that voice anywhere. “Vash?” he breathed.

“You haven’t heard the story of the fox and the crow, have you?”

“And the cheese!” Kraaia added.

Shosudin took another breath. The walls creaked at the touch of his hands.

“He’s speechless with anticipation,” Vash announced. “Let me begin. One time, there was a fox.”

“Once upon a time,” Kraaia groaned.

“Who is telling this story? As I said, there was a fox. And this one time, that I am telling you about, the fox was walking outside in the snow. And the fox – who was very handsome and clever, by the way – looked up and saw a crow high up in a bare tree.”

“With a cheese in her beak,” Kraaia added.

“Who is telling this story?”

Kraaia laughed. The muffled roar of the rivers seemed a gloved grip tightening around the place, or a heavier weight than stone. The heat was greater than the heat of deep earth. Shosudin felt lost in these caverns he knew well.

“The crow had a habit of taking things into her tree,” Vash said, “but this one time, she did indeed take a cheese. I will grant you that.”

“Shísím or shísrú?” Kraaia demanded.

Vash cocked his head. “Shísím, of course. A clever fox would not trust a shísrú that had been a long time in the beak of a crow.”

“Lena taught me,” Kraaia murmured to Osh.

Shosudin heard a crack and believed he saw a flash of light – or lightning – underground. He jumped, or Kraaia did, or they both did, since they were one.

Vash continued, “And the fox looked up at the cheese and said to himself, ‘That is such a handsome cheese, and I am such a handsome fox, so it can only be for me.’”

“That is a very Vash sort of logic,” Osh smiled.

“Who is telling this story?” Vash huffed. “As I said, this was a very clever fox, and he knew just what to do to trick the crow. He went to the tree and said, ‘Good day, good mistress Crow. How are you this one time and not any other time?”

Kraaia giggled. Shosudin tumbled and staggered into a clot – ropes and thorns and tendrils snagged at him, and he was seared and sweltering. He had found the break in the bone, but it burned like the sap of the snapped stem of a nettle. Kraaia’s giggles became a whimper.

“And the crow,” Vash said, “because she had a cheese in her beak, she could only say ‘Mmph!’ And the fox said, ‘What is that? How very kind of you to say!’ And the crow said again, ‘Mmph!’ with her cheese. So the fox said, ‘How handsome I am? Yes, I know!’”

“That is not what he said!” Kraaia protested with a shaky laugh.

“Who is telling this story? And the crow got angry and stamped with her one crow foot and not the other, and said ‘Mmph!’ And the fox said, ‘The handsomest creature you have ever seen? Mistress Crow, I am so flattered!’ And the crow got so angry that she stamped with both of her feet and opened her beak and dropped the cheese to say, ‘Handsome compared to a toad!’”

Something popped like an ember and a shower of red sparks burst into the place. Kraaia and Shosudin cried out at the same moment. The walls seemed to split everywhere, letting light leak in – bright, hot, blinding yellow-white light, the color of an August noon. Shosudin lifted his hand away and still could not see.

“Did it hurt a little, dídíla?” Osh soothed.

“He’s burning me,” Kraaia whimpered.

Shosudin looked to Vash, as always when he was uncertain. He saw the green of his friend’s shirt as a dark spot in a wavering wall of violet light.

Vash asked uneasily, “Shus?”

Gradually the forms and faces were coming clear again. He had simply stared too long at the sun.

Vash asked again, “Shus?”

“I do not burn you,” he said to Kraaia. “You burn me. I wish you would not.”

“Burn you?” Osh whispered.

“I did not!” Kraaia protested weakly.

“What do you mean, burn?” Osh asked in the elven language.

Shosudin looked to Osh. Vash did not. He was not smiling, but now it was his calm gravity that seemed false. He had to have heard. He had to have been wondering.

Shosudin shrugged. “Like Cat…” It seemed almost a lie: it was not as it had been with Cat at all, except in that it hurt and it burned.

“But you can…?” Osh prompted.

“I shall try.”

“What are you saying?” Kraaia whimpered.

“They are trying to guess what happened to the cheese in the story,” Vash said.

Kraaia smiled, and her leg relaxed. “The fox prob’ly ate it up in one bite.”

Vash turned and stared unsmiling at Shosudin until Shosudin bowed his head and laid his hands on the girl’s broken leg again.

“No, perhaps once upon a time, but not this time,” Vash said cheerily to Kraaia. “Instead he cut it with his knife and shared it with the crow, and he gave her some of his boiled toad skins also.”

Kraaia laughed in spite of the rising tide of pain. “And she stabbed him with her beak, and then they were even, the end!”

Vash shook his finger warningly at her. “The end, Mistress Crow… for this time!”

What a lovely post. Kraaa is so childlike in this chapter I just want to give her a big hug. I wonder if that's Shima in the bannar.....