A pall of snow lay over the shores of the lake now, but snow alone could not hush the pines. All through the night they sighed as deeply they always did, through all the year, through all the years.

There was nothing else on the lakeshore that the snow could have hushed. No animals came to the water’s edge now, for the edges of the lake were frozen. Indeed, this arm of the lake was frozen from shore to shore. Egelric wondered how far out the ice extended on the great lake that lay beyond this inlet.

He still slept in his small shack, and he still had no fire, but he had finally admitted the necessity of a door to keep out the wind. The wide lake did nothing to dampen the wind that roared down from the hills, and the thin stand of pines on the inlet’s opposite shore served only as a warning, for their sorrowful sigh would be lifted in a sharp gasp of surprise an instant before a blast of wind would strike him and his home.

It was a hard life, but he thought that it was right for him. He was being hardened and reduced by the cold and the austerity, like the fish he had caught before the ice closed in, and that he had hung outside from the eaves of the roof to freeze and dry.

He was growing wary and wise, like a dog who breaks away from men and returns to the wild; whose fat flesh melts away, leaving only ribs and sinew and muscle; and whose fur grows grizzled even as his eyes and teeth grow brighter and keener.

He still went up the hill to the site every day and worked with the men. He still did good work. He worked hard himself now, helping to lift the stones rather than merely pointing out the places where they should be laid. They still respected him. They had begun to fear him a little, too, he thought, when his eyes and teeth flashed. But the fear gave him a little extra mastery over them, and it was another strength.

He was close to something now. He thought he was close to some truth. He thought he was close to some understanding… an understanding of the nature of things… perhaps only of the nature of himself, but that might be all that a man could ever know. As he was hardened and reduced, as the flesh melted away, he felt that he was coming closer to the kernel of himself at the heart of all the accretions of thirty-four years of miserable, meaningless life.

It was not only his body that was melting away, although it was true that his ribs were growing evident and his beard was growing gray. His mind was being reduced as well. The great expanses over which his thoughts had ranged were being reduced to an ever smaller area, but it was all his own territory now. He had marked out the borders of it, claimed it, knew it, prowled it, and was even now circling in towards the skittish truths that bunched in the center of it, horns outwards, waiting for him and his keen teeth to arrive.

But there was Sunday.

Every time he closed in for the kill, there was Sunday morning like a breeze at his back, blowing his scent up from the hollow in which he crouched to warn his prey and send it stampeding away.

Sunday night, back at the shore, he would begin again the patient work of tracking and stalking and circling in. But he would need to work more quickly. Six and a half days were all he would ever have–

For there was Baby.

He still went to her every Sunday, and played with her, and listened to her chatter. As he listened, he thought on, and always he recalled the line from the Book of Isaiah: ‘The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb.’

But the time of which the prophet spoke was not at hand: he could not dwell with her. It was no life for a little girl, that he knew. He was no father for a little girl.

Like the half-tamed dog that ranges ever farther from the fire at night until one morning he does not return, he knew that he would eventually leave her behind – when she was ready for him to go.

She too needed a little hardening, but it could be done. She was with people who loved her, and would know how to care for her, and would not hurt her as he so often did. She was young and could get over him. She had very nearly reached the age he had when his father had left him forever, and he had survived. Moreover, she was with people who loved her. She had that advantage over the boy he had been.

But he would need to work more quickly. Six and a half days were not enough. It was already Saturday night. He had little time, and he was wasting it pondering what he was doing, instead of doing it.

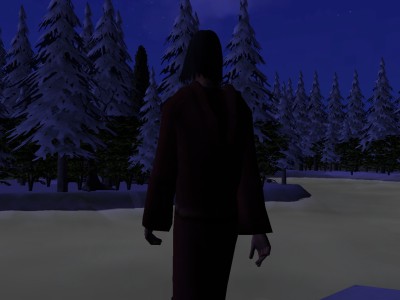

He stood.

The drifts of snow in the clearing were sharply striped with blue shadow, and the pines all around cast blurred blue-black shadows taller than themselves, but the smooth expanse of lake ice was blank and blue-white beneath the brilliant light of the full moon.

He knew the lake stretched far to the south, though from here it was hidden behind the pines. He knew that the whole surface of the lake must be one pure, featureless, shadowless plain of ice. It must be as bright as the moon, reflecting all of its light like an enormous mirror. In such a mirror one might see the very face of God.

Walking on such a surface must be like walking on the moon itself, he thought. His father had walked on the moon as a boy, and sunk in up to his knees. But Egelric did not think he would sink. The ice was hard and bright as a mirror.

What might a man not see when walking on light itself? The shadowy pines on the shores would be blotted out by the light; there would be no shores; there would be only the light. He himself would be blotted out by the light. He would be a tiny shadow moving across the face of God.

Egelric left the shore and stepped out onto the ice.

Only the very edges of the ice were coated in snow; the rest of the lake had been blasted clean by the wind roaring down into the valley. After only a few steps, he did not even leave footprints behind.

A little farther and the light blurred the form of his body and then blotted him out.

Back on the shore, the pines gave one sharp gasp of surprise and then fell back into their deep, nightlong sigh.

He's not planning to kill himself, is he?