Egelric poked at the ashes of his fire with the toe of his boot. It hadn’t burned well or long, and it hadn’t done much to dry his clothing. His cloak was now damp and reeking of smoke instead of merely wet, and the rain was beginning to fall again. At least it had stopped long enough to allow him a fire.

He went inside and lit the lamp.

It mattered little that his clothes were still damp. Everything was still damp. The fog that hung over the lake had soaked into his bedding, into the wood, into the walls, into his skin.

He would sleep in the damp and wake with an ague. It mattered little.

The best thing would be to die before they found him. He had his knives. If he had been more of a man, he could have managed it without the ague. But if he had been more of a man, he might have deserved to live.

He closed his eyes and listened to the light rain on the roof, its whisper punctuated from time to time by the fat drops that fell like tears from the branches of the overhanging pines. They were so much sadder than a sigh.

Then he heard the door open, and quiet feet step inside, and the door close.

They had already found him. He would have to go back tonight.

But the visitor did not move or speak. He thought he must appear to be asleep.

Then he wondered whether it were not simply a woman. He thought it might be rather satisfying to butcher her, as long as he meant to kill himself at the end of it anyway, and since it wasn’t possible to butcher every last living one of them.

“You take your life into your hands tonight,” he muttered without opening his eyes.

“I know it, but I must speak with you.”

He knew that voice and that purling accent. It was no woman, but an elf.

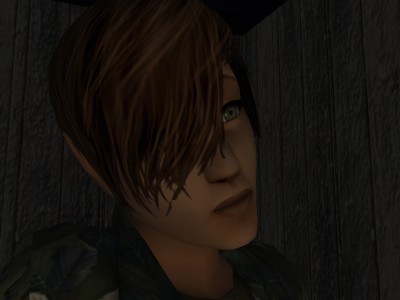

“Verily the last mortal I thought to meet tonight,” Egelric sighed, and he opened his eyes.

The boy grinned. “If you had been expecting me, I would be worried.”

Egelric sat up. “I suppose I had many questions for you, but I don’t have the heart for it tonight. And it doesn’t matter. I wish you would leave, and we shall pretend you never came.”

“You sound troubled.”

“Oh, for God’s sake, Ears, get out of here! The devil! Is it your life’s purpose to save mine?”

“You weren’t thinking of drowning yourself again?” he asked cautiously.

“No. I rather supposed that if I hadn’t the courage for knives, the ague would suffice.”

“This won’t do. What about your daughter?”

“My daughter will, as I think you realize, be happier without me.”

“Is that why?”

“I don’t know why I am talking to you.”

“Neither do I, but I am pleased you do talk to me. Your daughter would be very unhappy without you. She already is.”

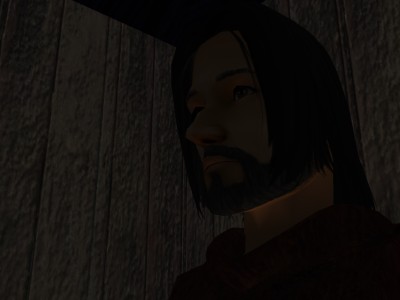

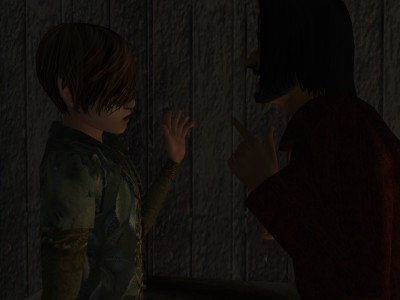

Egelric rose and found that, although the boy had grown, he was still the taller of the two. “You did understand that I have my knives tonight?”

“I know. But I must speak with you about your daughter.”

“My daughter is not your affair.”

“She is an elf, and you are only a man. You don’t know how to care for her, and I am here to tell you.”

“You might begin by telling me who is this woman who is killing elves?”

“Oh – what do you know about that?” the elf asked warily.

“Perhaps more than you. She attacked my daughter last month.”

The elf gasped and threw up his hands, almost as if he had been struck.

Egelric was surprised to see him so affected and decided to press him hard, now that he had him off-balance. “Who is she? Where did she come from? What does she want?”

“Was she hurt?” the boy pleaded.

“I don’t know. She’s alive, but she won’t speak to me about it. How would I know?”

“Is she – I don’t even know…” he said weakly. “What happened?”

“A boy found the two of them struggling and stabbed the woman with his knife. My daughter fled into the fire. Did you know about this?”

“I knew nothing. We only wondered why no one had been killed that night…”

“Did you know that fire cannot burn her?”

“I knew that…”

“What else do you know? It’s time you told me what you know.”

“I suppose that’s why I am here,” he said, coming out of his daze. “I came to tell you that you need to allow your daughter to go outside, into the woods. She can’t be kept in a castle all the time. She needs to be among the trees.”

“Someone tries to kill my daughter, and you tell me I need to let her outside more?”

“Not at night! Rather, not on the night of the new moon. You should have known that!”

“I wasn’t here. And she was not to have been allowed outside, but she sneaked out when there was a fire in the court of the castle.”

“When… oh…”

“Now tell me, elf – this woman, is it Hel?”

The elf blanched and stepped backwards, as if again struck.

“I know more than you thought I did,” Egelric observed with a satisfied smile.

“I… indeed,” the elf quavered. “What do you know?”

“You need to tell me how I can protect my daughter.”

“I don’t know. If we knew, don’t you think we would protect ourselves? She kills one of us every month.”

“That’s funny,” Egelric snorted. “Your Druze and Midra killed one of us every month for a good while.”

“They don’t any longer.”

“No. Why did you release them?”

“I truly can’t talk to you about this…”

“You’ve already said too much. You might as well continue – if you want to help my daughter.”

The elf swallowed nervously and bit his lip. Egelric saw him hesitate, and waited.

“If you see Druze or Midra again, don’t disturb them,” the boy said finally. “They aren’t interested in hurting you any longer.”

“Are they too interested in hurting the woman?”

“Yes.”

“Wish them good hunting. Now, tell me about the Dark Lady,” Egelric said, expecting to see the boy falter again. He was not disappointed.

“What do you know about that?”

“Tell me about the dragon.”

The boy cowered before him. “What do you – ”

“No! What do you know about that?”

“How is it possible?” the elf whispered.

“I spoke to the Dark Lady. I saw the dragon – it sat itself down right in front of this shack and stared me in the face with its great yellow eye. Now!”

“It’s not possible…”

“Then tell me how the devil I should even know about them?”

“Who told you?”

“Damn you! No one told me, I want you to tell me!”

“But why didn’t they kill you?”

“Well! Why do you suppose?”

“I don’t know…”

“The Dark Lady said it is forbidden to hurt me. How do you suppose I faced Druze and Midra and survived?”

“But the – the dragon…?”

“May the dragon hurt me?”

“I… don’t know…”

“The devil you don’t! What do you know?”

“Only this – that you and I are not enemies. You must not work against the elves. Why did you release Hel?”

“Why? We didn’t mean to. We didn’t know anything about her. Some children claim to have found her, and released her without knowing.”

“Where was she?”

“In the catacombs beneath the church.”

“Oh! You mustn’t allow her to enter the crypt beneath the castle.”

“What? Why?”

“I don’t know. It is Druze who said it.”

“Druze,” Egelric muttered.

“He’s not your enemy now. We aren’t your enemies. Please don’t forget that.”

“You still have my son.”

The boy sighed. “I wish it weren’t this way.”

“Tell me about him.”

“I shall tell you how your son is, if you tell me how my – ” He stopped with his mouth open, apparently searching for another end to his phrase.

“Your what?” Egelric growled. “If you are speaking of my daughter, I should like to know what she is to you.”

“My – fellow elf.”

“That won’t do it. Out with it, boy.”

“She is my cousin,” he admitted softly, defeated. “And I am a fool.”

Egelric stared at him for a moment. This boy was related to his daughter by blood. Next to him, Egelric himself was a stranger to her. “God help you if she ever learns it,” he said. “I am a jealous man.”

“You would allow no one else to love her?”

“Don’t ever let me hear you say you love my daughter.”

The elf stared sorrowfully down. “Your son is very well,” he murmured. “He is learning to speak your language now. He played often in the sun this summer, and he is beginning to have freckles on his nose and cheeks.”

“Like his mother,” Egelric whispered, awed by the idea.

“He doesn’t suck his fingers any longer, but he still has Toes and Ears. And he is a very talkative little boy. Now, I believe I should go.”

“Your cousin is not very well,” Egelric said. “She is very unhappy, and it is my fault. As you say, I am only a man.”

The boy looked up at him at last. “You should let her go out more, and you might be surprised at the difference it will make in her.”

“How can I? The people are afraid of her, and the – this Hel woman wants to kill her.”

“Hel can’t bother her in the daylight, and the people… The elves are watching over her. She won’t be hurt, though I admit she may be teased. But it is more important that she be out in the sunlight and among the trees.”

“You’re asking me to trust her to the elves?”

“I suppose so.”

“That is precisely what I should least like to do.”

“Then let her go out with her friends. Or take her out yourself. But she must go out. If you lock her up long enough, she will die. She will die as surely as a tree that you might uproot and bring indoors. It is to tell you this that I came. Now I wish I had written a letter, for I have said far, far too much.”

“I wish you hadn’t come.”

“As do I. Let us try to see that some good comes out of it?”

“Aye.”

“And don’t let it be the last time we meet.”

“If the ague doesn’t kill me.”

“And my father doesn’t kill me,” he sighed, and turned to open the door.

“The peace of God on you, Ears,” Egelric muttered.

The boy paused and looked back at him, apparently surprised and, perhaps, touched. “And on you, Egelric,” he said, and he went out into the rain.

I still wonder what was that dragon ...