“Lena!” the elf whimpered.

“Yes, Lord?” Lena called from the kitchen.

“She’s coming!”

“I hope she is,” Lena murmured and returned to her stirring.

“No, this time she truly is! What shall I do?”

He heard the spoon fall against the rim of the bowl, and Lena came into the hall.

She explained patiently, as had been patiently explained to her: “You shall bow, and kiss her hand, and ask her: ‘How do you do?’ And she will curtsey, and say: ‘I am well, tank you’, and ‘How are you?’”

“I know that,” he whined. “But then what shall I say? I shall surely say something foolish.”

“She will think everything you say is clever and wise, because you are her husband. You will see.”

He brushed off his sleeves and straightened his tunic, muttering, “Anyway, she’s probably only going up to the castle to visit the Duchess.”

“I think she will not come to the castle again without seeing you.”

“She’s coming this way!” he gasped.

“I told you,” Lena giggled.

“I don’t have any baby spit on my shoulder, at least?” he asked gruffly.

“On your shoulder, no…”

“Lena!”

“Nowhere, nowhere!” she laughed and turned away. “I shall go up in the loft and tell Penedict to be quiet.”

“Don’t you laugh at me up there! I shall hear you!”

He heard her laugh all the way up the ladder. He almost wished he could follow her.

He could hear Catan calling out to the guards and various other persons as she walked across the court, but he was surprised to hear that no one else was with her—not Alred, as he had expected, nor her sister, nor Egelric or Lord Cynewulf, nor anyone else who had ever set foot in the old barracks. If she was alone, he thought, then it would be easier. Or, perhaps, much harder.

But when she knocked, he opened the door without incident, and she said brightly, “Good afternoon, Friend!”

“Good afternoon, Cat! Come in.”

He stepped aside so that she could enter the hall and he could close the door behind her. She was here! He smiled at her, amazed that anything could be so simple between them.

And then he realized he had no idea what to do or say next. Fortunately he remembered what Lena had said, and though he could not risk groping after her hand to kiss it, he was able to bow and ask, “How do you do?”

“Middling fair,” she trilled, but her voice made her seem merrier than she was admitting. He heard a swish of skirts that he supposed was a curtsey. “And how are you?”

“I am well, thank you.” Then he remembered that that was what she was supposed to say. Now he was thoroughly confused, and Lena had not told him what he was supposed to say next at all!

“This is a very nice house!” Cat was saying admiringly. “Snug and warm for such a big house.”

He gasped. “Are you hot? Are you too hot? May I take—I mean, do you have a cloak? May I take it if you do? Have one? And are hot? Are you?”

“Aye… I mean, no!” she laughed. “I am not too hot. But you may take my cloak.”

“Thank you.”

“Thank you.”

He had to let her struggle out of her cloak alone, for fear that his blind fumbling would only make it more difficult for her. But he could easily carry it to the hook: he knew his “big house” well.

“Of course, I don’t mean to stay here,” he said quickly, fearing she was seeing herself in the house already.

“No?”

“It’s quite noisy here in the courtyard for ears such as mine. And I don’t need the walls, you know. I can defend my own house.”

“You’re not going back to the elves, are you?” she murmured.

“No! Nor back to my cave, either. I shall build a new house, and live in a house, just like any man. Who is blind, and has pointed ears, and can heal little children with his hands.”

He laughed, and to his relief she laughed with him. However, he realized he had stopped walking at some distance from her, and he did not know under what pretext he could now cross the remaining space. He could only stand grinning foolishly at her, and hope she was smiling back.

“I heard about all you have done,” she said. He imagined a smile as wistful as her voice. “I think it is perhaps the most wonderful thing I have ever heard, outside of the lives of saints. Even including the lives of saints.”

He smiled and scratched his head awkwardly, and through some graceless fidgeting of legs and elbows he found himself a few steps closer to her by the time he mumbled, “It was not much to do. It was no miracle.”

“Now, Alred told me that you made your own self very ill.”

“What is that compared to the death of a child?”

“So long as it doesn’t lead to your own.”

Was she trying to say she didn’t want him to die? That was something. That was something more than he had had all through the last month.

“I’m still here,” he shrugged.

Now she advanced a few steps, and though they didn’t quite bring her to his side, they were not hesitant.

“Promise you won’t try to do more than you can.”

“Don’t worry about that.”

“Promise me and I won’t.”

His hand went out to her, though she was still too far away to touch. Or perhaps that was why. Certainly, when she stepped still closer to him, he pulled it back again.

“I promise,” he bowed.

But she kept coming.

She stopped before he could feel her skirts brush his legs, but a moment later he felt her hands come creeping up onto his shoulders.

For an instant he believed she must have air nature, for he was utterly unable to breathe. Then he thought she must have earth nature: he could not move at all.

Then he realized she had fire nature. It was she who was teasing up the fire in him to dance beneath her fingertips. Perhaps she did not know she was doing it, but he knew he wasn’t—he was too frightened of frightening her.

“I’ve been wanting to come and thank you,” she murmured. “Perhaps I should begin by thanking you for saving me.”

“No…” He shook his head, and that movement seemed to free up the rest of his body. He was able to lay a hand on her own shoulder.

“Vash thought it must have killed you. You must have thought so, too, mustn’t you?”

“I never thought at all,” he smiled ruefully. “I don’t always think before I act. I always believe myself remarkably clever at the time, however.”

“I’m afraid I have the same flaw,” she giggled nervously.

He found the courage to lay a hand on her waist. She was so close that, in addition to the fire in her, he could feel the simple animal heat of her body.

“I never said it was a flaw,” he sniffed.

She laughed, but when her laughter threatened to turn into a sob, she pulled him against her and herself against him. She laid her head on his shoulder and choked, “Alred says you’re so kind and so—so funny! Why have I been so sad in my room all this time when you’ve been here to make me laugh?”

If he had known it would be this easy, he might have sent Lena and Benedict away for a visit to the reeve’s wife.

“Are you stubborn, too?” he asked her.

“Do you mean ‘stubborn, too’ in addition to not thinking before I act, or ‘stubborn, too’ because you’re stubborn, too?”

“Both.”

She laughed and squeezed him.

Now they were too close to see one another, and it did not matter that he was blind. She was warm and soft all over, and far more comfortable to hold than he had imagined. He was delighted to learn that her hair did have a scent after all: a faint perfume of yarrow and sweet gale, and beneath it the grassy odor of her warm skin, like ripening wheat in the sun.

Vash and others had told him that her hair was black, but he had been blind long enough that he no longer truly cared. It was as light and silky as his mother’s, and he told himself that soon he would fall asleep with that cool cloud against his cheek and that perfume of meadows in his nose.

“Fortunately for you, I’m also polite,” she said. “I had to come in person and thank you, since you gave me a gift.”

“That’s not what I meant to do.”

“Perhaps not, but I’m glad you did.”

“Then so am I.”

“What is it, in truth?”

“Only a pebble.”

“Ach! Only a pebble full of light and ‘sparklies’, as the Old Man calls them.”

“You’re the one ‘full of light and sparklies’. The pebble is only a pebble.”

“I don’t understand.”

“It’s magic.”

“That’s not an explanation!”

“I shall have to tell you the whole tale to explain it to you. It’s a pretty story, but tales are properly told at night, around a fire, and not standing in a hall in the middle of the afternoon.”

“I shall come back when it gets dark,” she teased and tried to pull away from him. He was bold enough by now to hold her tight.

“Or you can stay here until it does.”

“But I don’t have my pebble with me.”

“We don’t need it.”

“Ach! It has done its duty, has it? It brought me here!”

“I told you, that was not what I meant to do with it.”

“What did you mean to do?”

“I meant for you to think about me,” he murmured.

“Oh!”

“So I sent you a little stone to make a faint light. Because I wanted you to think about me when you were alone, and when it was getting—dark—Cat!”

She had suddenly begun struggling against him, so startling him that she was able to burst free of his arms and fling herself back. Now he was blind again, in every way.

“Cat!”

She was moaning behind her hand.

“Cat! What did I say? What did I do?”

He thoughtlessly followed after her, and she continued backing away. The moment she found herself backed into the corner, the moment her elbows hit the walls on either side, she screamed once, a piercing cry like a rabbit beneath the claws of an eagle.

He cringed away from her, and she slipped out, so intent on keeping a broad space between them that she dragged her body along the rough stones to the door. Outside she ran, and he could hear her skirts billowing like flags, and then only the sound of her boots on the frozen ground, and then nothing but the confused calls of the men in the court.

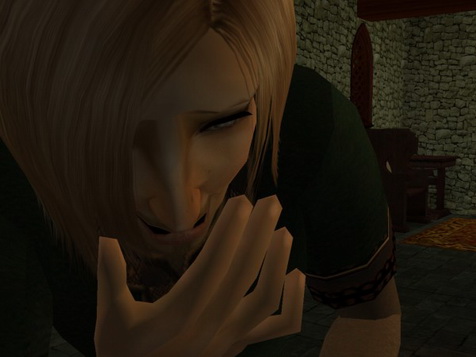

He could scarcely breathe, though it was not due to the influence of some elf with air nature, but to a stabbing pain in his ribs. Nor could he stand. He would never breathe deeply again. He would be hunched over and crippled forever.

At last he was able to croak, “Lena!”

Lena came.

“What did I do?” he whispered.

He realized that Cat had left without her cloak, and his guilt was multiplied. The pain too was multiplied, and he understood that they were one and the same.

“She went out without her cloak!” he sobbed. “She went out into the cold because of me!”

“What happened?” Lena asked him.

“I don’t even know! What did I do?”

She laid a hesitant arm over his shoulder, as if she were unsure whether she could call herself his friend, but finally decided he needed one regardless.

“She has been greatly hurt,” she soothed. “You must be patient with her, as Alred says. She will come again.”

“Never!”

“She will. She loves you.”

“No longer!”

“She does,” Lena sighed. “Didn’t you say you were afraid to love her for so long, even though you already did?”

He supposed he had said it, but he did not care to admit it again. He sniffled.

“Now she is afraid, even though she already loves you. You must give her time, Lord. She will come again.”

If anyone is wondering what the heck just happened here, I refer you to this chapter and this one.

Too bad poor Kiv doesn't have access to the archives.