Gunnilda whispered, “Ethelmund.”

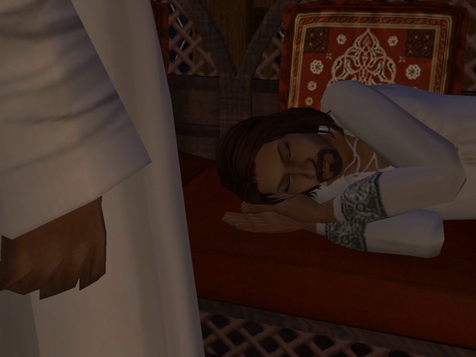

Ethelmund did not stir.

“Ethelmund. You fell asleep on the couch.”

She felt queer about touching him. She felt queer about speaking loudly. She wanted him to wake up, somehow, on his own.

“Ethelmund,” she whimpered.

“What?” he groaned.

“You fell asleep on the couch.”

“I know that,” he sighed.

“Well, I wish you would come up to bed.”

“Why?”

“Well…”

She wanted him to come up to bed because that was the normal thing to do. It wouldn’t make their life normal again, but it would give it something of the appearance. If only he would act normally – and if only she did not think too hard – she could feel a little better about him. It would be some comfort to her even to pretend.

She wanted him to come up to bed because she was in it, and she thought her body might have been some comfort to him. If that would be enough, she would give it gladly. Even if that would help only a little, only for a moment, she would feel that she had done something for him.

“It’s cold down here,” she said.

“I have the fire.”

“But you don’t have a blanket or anything.”

“I would be grateful if you would get me one,” he muttered.

“But, Ethelmund. If you would just come to bed…”

He sighed. That gave her nothing to answer and nothing to ask, so she sat herself down on the floor beside him.

He sighed again and sat up slightly to lean on his elbow.

“Well, maybe I’ll just sit here with you and the fire for a while,” Gunnilda said. “I don’t know but I guess I’m not so tired either.”

He said nothing. He appeared half-asleep and half-annoyed.

“Ethelmund,” she blurted. “I have something I’ve been meaning to tell you.”

He did not respond. Meanwhile her heart was pounding. She had startled herself, frightened herself. Normally she would not have told him so soon, but nothing was normal any more.

“Well, I’m fairly certain I shall be having a baby in the harvest season.”

He did not twitch so much as an eyelid. This was more frightening than anything.

She tried to think of some comment she could make herself. “It’s a busy time of the year for that sort of thing. I never did have a baby in the full harvest time. But I guess we’ll manage.”

“Why are you telling me this now?”

Her heart bucked and galloped. “Well…” she whispered.

Finally he roused himself enough to reach down and take her limp hand between his fingers.

“That’s good news, Gunnilda,” he said dully.

The words were empty, but they had something of the appearance of rejoicing. She would have to content herself with that.

“Isn’t it?” she asked eagerly.

“I guess I won’t have to come to bed for a while, then.”

Her heart began to stagger and leap again. “What?”

“If you’re pregnant.”

He did not elaborate, so after a moment she whispered, “What?”

“I don’t have that for an excuse. So you can sleep in peace.”

“Ethelmund…”

“That’s what you want, isn’t it?”

“But… but you don’t need an excuse.” Her throat was parched. She wished she could step away to get a drink, but she supposed he would be asleep by the time she returned. “You’re my husband, Ethelmund,” she croaked.

“So I can do whatever I want, is that it?” he muttered.

“I…”

“What if I don’t want?”

She had nothing left – he did not want her body, and she had used the news of the baby to no effect. She could only go on preparing his meals and mending his clothes and caring for his remaining children, keeping up the appearance of a normal life from her side. She could only hope he would find his own way back to it.

He lifted his arm slowly, as he would swing a beam into place, and he laid his broad hand on her shoulder. “I’m glad for you, Gunnilda, if you’re happy about your baby.”

He stared at her through half-closed eyes, as if he had used his last strength in making this one gesture and now found even his eyelids heavy. His hand slid from her shoulder and hung over the edge of the couch until he slowly drew it back up beside him.

“Would you bring me a blanket, please?”

I often wonder why she married that man.